Isabel Allende famously said that “erotica is using a feather, pornography is using the whole chicken”. For the most part, Walerian Borowczyk favoured the feather.

|

| Immoral Tales (Contes immoraux, 1974) |

It’s impossible to discuss Borowczyk’s film work in any depth without acknowledging that the vast majority of his post-1973 output can be described as ‘erotic’, much though the director himself bridled at the label (“If someone mentions the word ‘erotic’ or says I make erotic films, it’s always with ironic innuendo or a feeling of denigration”). One upshot of this was a vertiginous fall from critical grace - even those who praised the films for their lustrous imagery seemed reluctant to engage with their content, as if there was something shameful about even admitting to having watched them. Another was that it became increasingly hard to see Borowczyk’s films as their creator intended, particularly in censorious countries like the UK. The version of The Beast (La Bête, 1975) that opened in London in 1978 is virtually incomprehensible at times, as was the British edition of Docteur Jekyll et les Femmes (1981), retitled The Blood of Doctor Jekyll. In both cases the cuts removed sight of the enormous (albeit prosthetic) phalluses sported by the titular beast and the rapacious Mr Hyde, and few of his other films escaped untrimmed.

|

| House (Dom, 1958) |

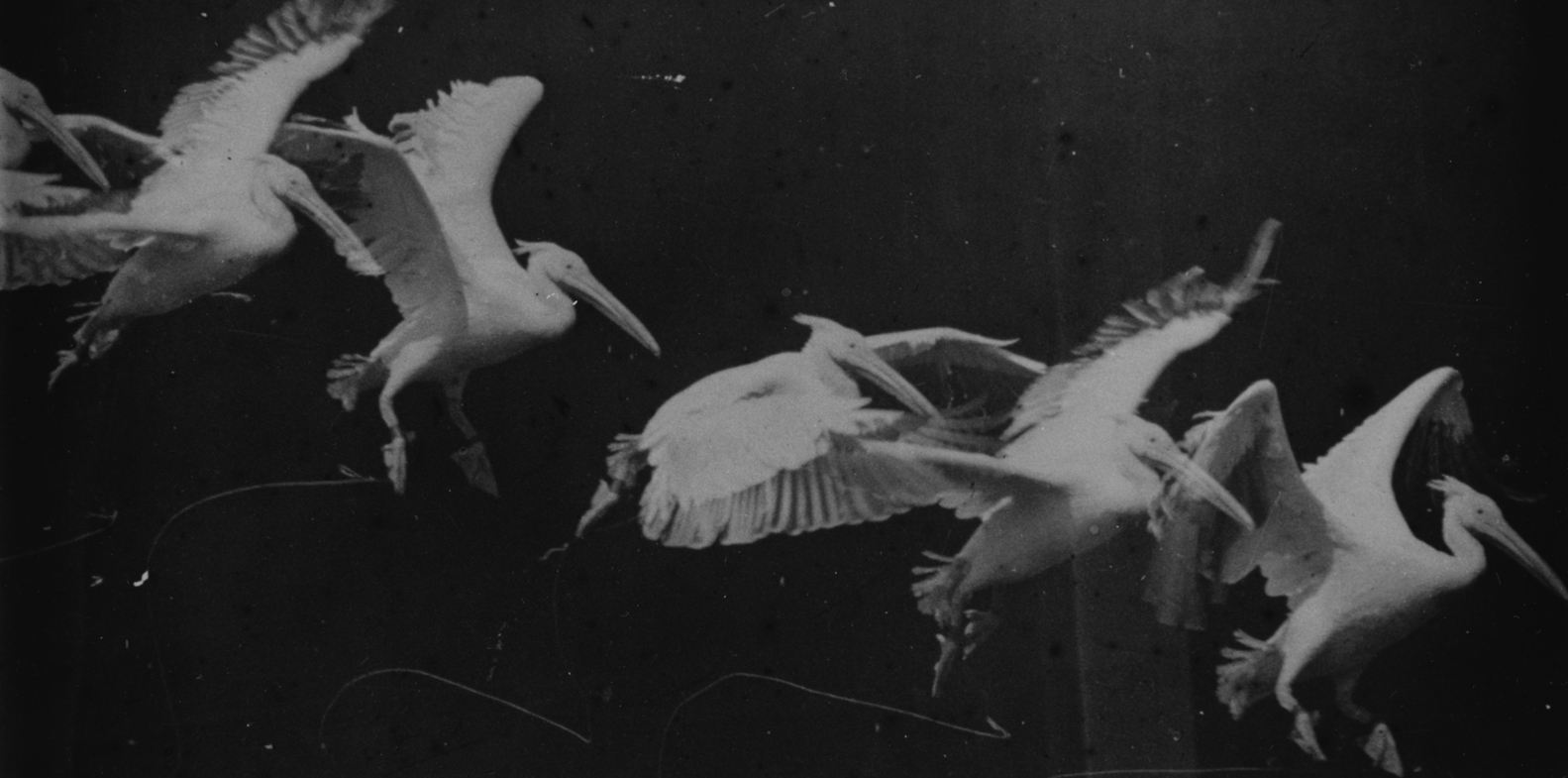

Borowczyk’s interest in the erotic can be discerned from his earliest films. Both the unnamed hero of Astronauts (Les Astronautes, 1959) and the hen-pecked husband in The Theatre of Mr & Mrs Kabal (Le Théâtre de M. et Mme Kabal, 1967) sneak occasional peeks at semi-undraped beauties, while many of his early films are suffused with a weird fetishism: the animated wig in House (Dom, 1958) or the fusion of sexualised body parts and industrial apparatus in Angels’ Games (Les Jeux des Anges, 1964). His first two live-action features, Goto (1968) and Blanche (1971) both contain full-length female nudity, albeit briefly glimpsed compared with what came later.

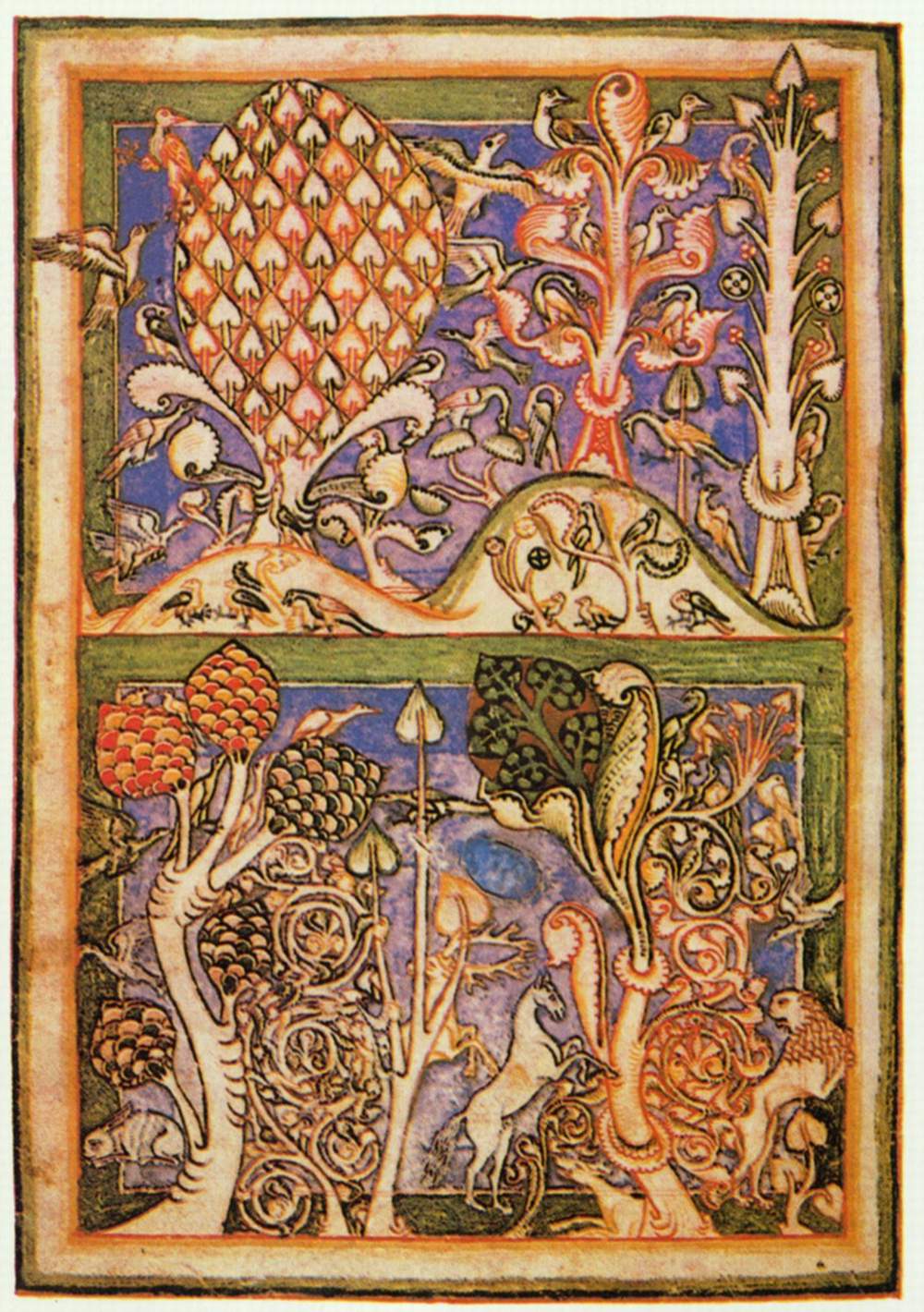

The watershed period was 1972-4, when Borowczyk made the six short films that were part of his original conception of Immoral Tales (Contes immoraux, 1974) - the four films that comprise the final film, The True Story of the Beast of Gévaudan, which became the dream sequence in The Beast, and A Private Collection (Une Collection particulière, 1973), which explored vintage erotic paraphernalia owned by André Pieyre de Mandiargues (see below).

The latter exists in two versions: the more familiar 12-minute cut, and the 14-minute ‘Oberhausen’ version after the festival where it debuted. Whereas in the shorter cut, fingers and thumbs would conceal risqué and outré material, in Oberhausen everything was laid all too bare, and the inclusion of a piece of vintage film featuring unsimulated intercourse between a woman and a dog has made this version legally undistributable in several countries. Simulated bestiality also occurs in The Beast and the middle story of Immoral Women (Les Heroïnes du mal, 1979), while other controversial (often recurring) subjects include female masturbation, incest, rape and explicitly eroticised ritual sacrifice.

|

| A Private Collection (Une Collection particulière, 1973) |

The latter exists in two versions: the more familiar 12-minute cut, and the 14-minute ‘Oberhausen’ version after the festival where it debuted. Whereas in the shorter cut, fingers and thumbs would conceal risqué and outré material, in Oberhausen everything was laid all too bare, and the inclusion of a piece of vintage film featuring unsimulated intercourse between a woman and a dog has made this version legally undistributable in several countries. Simulated bestiality also occurs in The Beast and the middle story of Immoral Women (Les Heroïnes du mal, 1979), while other controversial (often recurring) subjects include female masturbation, incest, rape and explicitly eroticised ritual sacrifice.

|

| Immoral Women (Les Heroïnes du mal, 1979) |

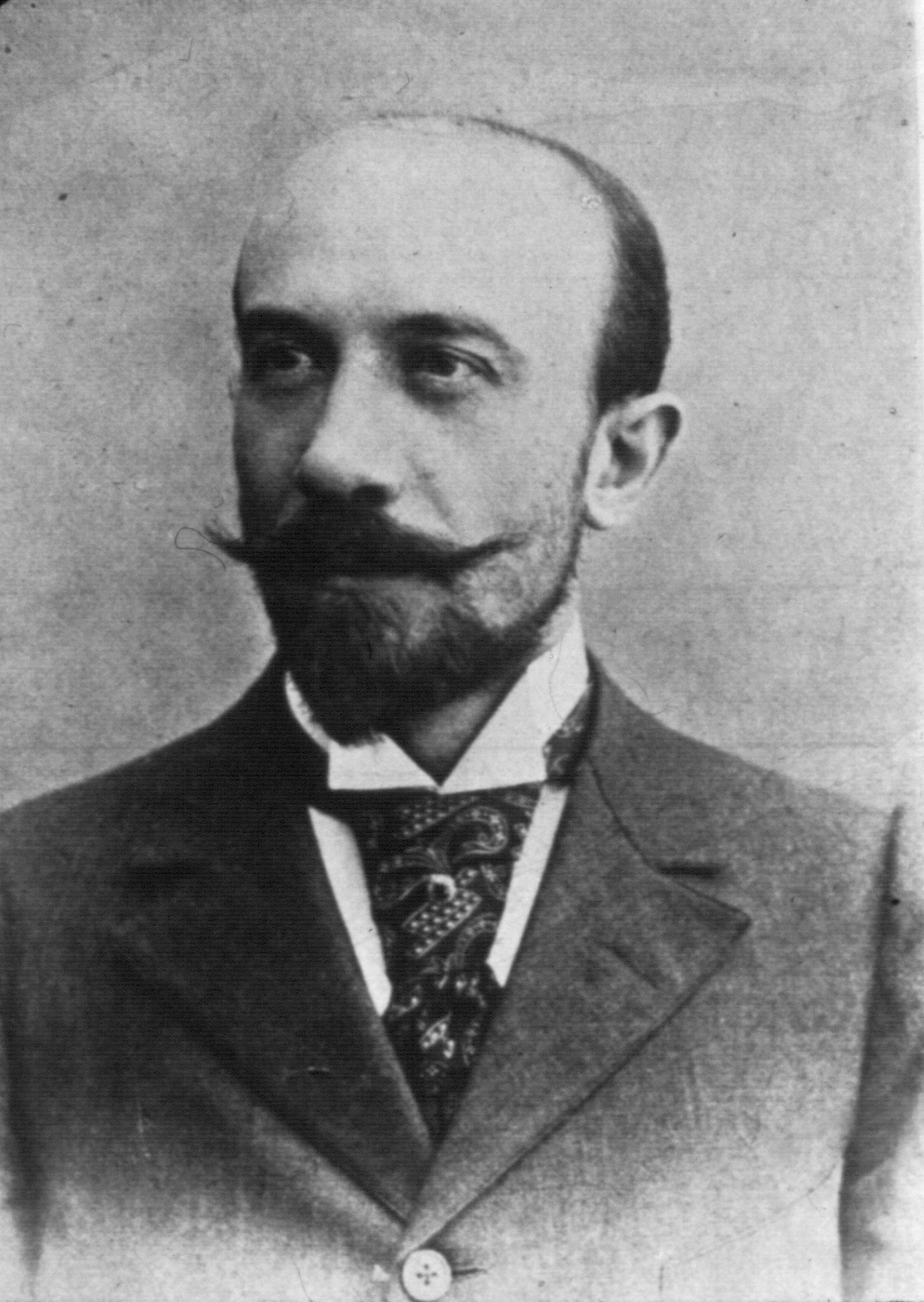

Borowczyk’s collaborators during this period include the French Surrealist writer André Pieyre de Mandiargues (1909-91) and his wife, the Italian painter Bona Tibertelli de Pisis (1926-2000). Bona's images, populated by creatures possessing both human and mollusc characteristics, are celebrated in Borowczyk’s short film Venus on the Half-Shell (Escargot de Venus, 1975), while her husband wrote the source texts of several Borowczyk films: La Marge (1976) was based on the eponymous Prix Goncourt-winning novel, Love Rites (Cérémonie d'amour, 1988) on Tout disparaîtra, while Immoral Tales and Immoral Women included two of his short stories (‘La Marée’ and ‘Le Sang de l’agneau’).

Borowczyk’s other erotic films also had distinguished literary sources: The Beast was inspired by Prosper Mérimée’s novella Lokis, Behind Convent Walls (Interno d’un convento, 1977) by Stendhal (the article ‘Promenades dans Rome’), Lulu (1980) by Frank Wedekind’s play, Dr Jekyll by Robert Louis Stevenson, while The Art of Love (Ars amandi, 1983) features the poet Ovid as a central character. (Borowczyk also depicted the painter Raphael, Erzsebet Báthory and Lucrezia Borgia as film protagonists). At the turn of the 1990s, Borowczyk adapted four works of classic erotica into half-hour episodes for the French TV series Série Rose.

None of this prevented him from being frequently dubbed “that arty pornographer”, although his erotic films defy that overly simplistic label. On the most basic level, they lack the continuum that is the essence of true pornography. Anyone using his films for sexual gratification is likely to be frustrated by his constant framing of seemingly important details just off camera, or cutting away at equally crucial moments - often to a loving close-up of an inanimate, often antique object. (Sight & Sound, one of the few English-language publications that remained broadly sympathetic to Borowczyk, asked of Dr Jekyll, “Who else would think of draping a girl over a treadle sewing-machine as an image of erotic invitation?”).

More importantly, Borowczyk delves beneath the surface in a way that pornographers rarely feel the need to do. Although his features are invariably populated by exceptionally attractive and frequently unclothed young women (incarnated most memorably by his wife Ligia Branice, Paloma Picasso, Sylvia Kristel and Marina Pierro), it’s equally clear that he takes as keen an interest in their psychology and their own all too palpable desires, whether the entrapped naïfs played by Branice (the 1966 short Rosalie, the features Goto and Blanche) or the altogether more knowing and assertive women played by Pierro in the later films.

None of this prevented him from being frequently dubbed “that arty pornographer”, although his erotic films defy that overly simplistic label. On the most basic level, they lack the continuum that is the essence of true pornography. Anyone using his films for sexual gratification is likely to be frustrated by his constant framing of seemingly important details just off camera, or cutting away at equally crucial moments - often to a loving close-up of an inanimate, often antique object. (Sight & Sound, one of the few English-language publications that remained broadly sympathetic to Borowczyk, asked of Dr Jekyll, “Who else would think of draping a girl over a treadle sewing-machine as an image of erotic invitation?”).

|

| Docteur Jekyll et les femmes (1981) |

More importantly, Borowczyk delves beneath the surface in a way that pornographers rarely feel the need to do. Although his features are invariably populated by exceptionally attractive and frequently unclothed young women (incarnated most memorably by his wife Ligia Branice, Paloma Picasso, Sylvia Kristel and Marina Pierro), it’s equally clear that he takes as keen an interest in their psychology and their own all too palpable desires, whether the entrapped naïfs played by Branice (the 1966 short Rosalie, the features Goto and Blanche) or the altogether more knowing and assertive women played by Pierro in the later films.

|

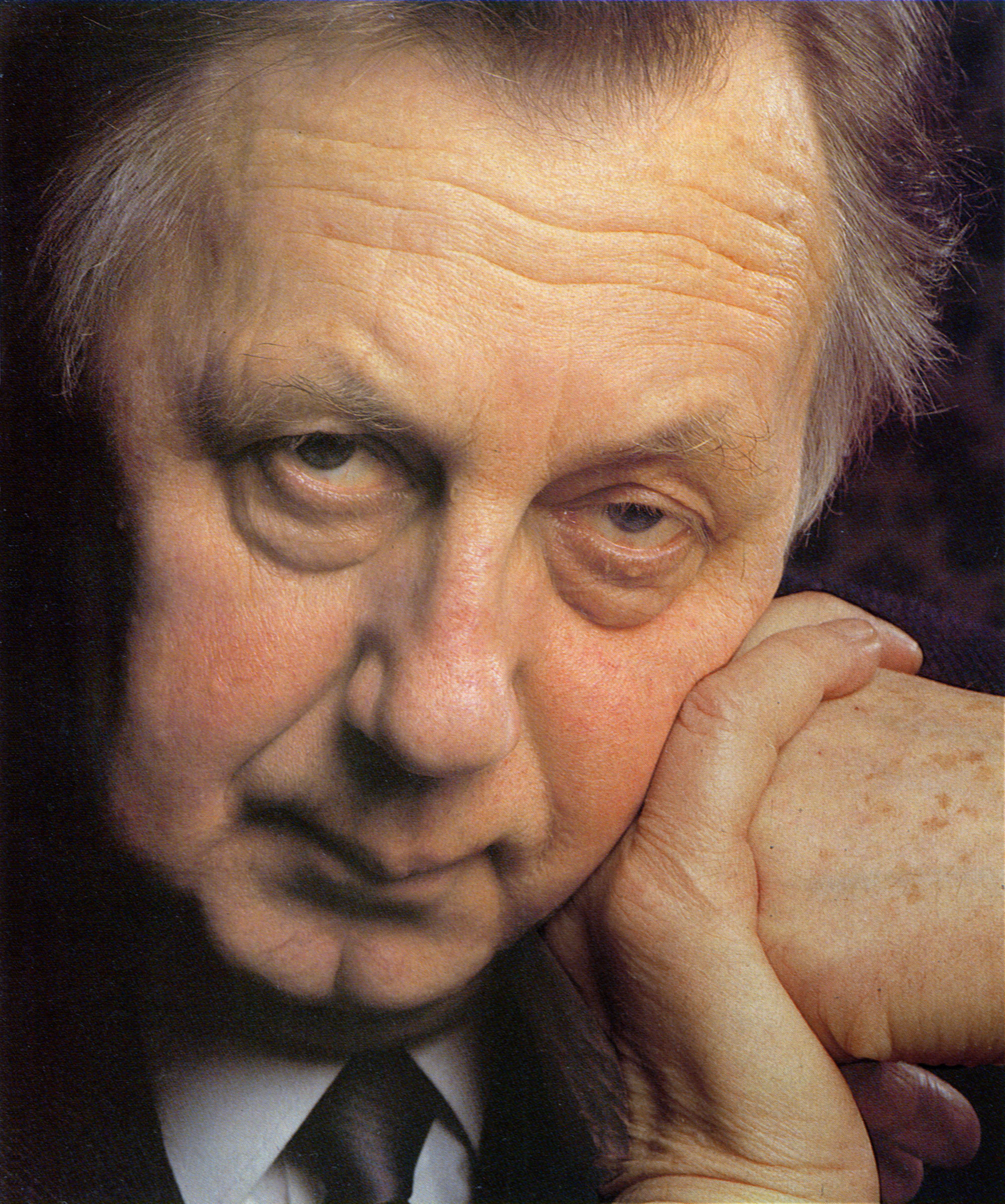

| Borowczyk the voyeur |

While it’s hard to forget that we’re looking through the eyes of a middle-aged voyeur (Borowczyk was already in his fifties when Immoral Tales opened), he was cheerfully honest about this, responding to a charge that he was simply a pervert with the reply that he was merely echoing people’s existing fantasies. But it’s this constant tension between the desires of the observer and the observed that give his films an erotic charge that remains almost unmatched in cinema.

MB